L-tessellatum-idruntino

A floor mosaic made up of a myriad of small tiles

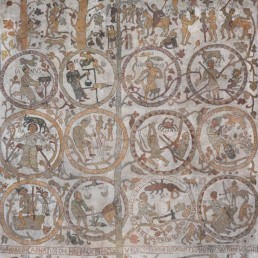

The floor of the Basilica is a “talking” floor, as it is designed to be read as a book made of stone. Deemed by some a “Medieval visual encyclopaedia”, the mosaic is a true masterpiece thar combines theology, worship, culture, scholarship, myth and aesthetics.

It is a vast floor covering, stretching 52 metres in length through the nave, the presbytery and the apse, fanning out into the arms of the transept to form a cross, thereby recalling the Christ-centric motif of the entire work.

The whole mosaic consists of a myriad of tiles made with local limestone (approx. 600,000 in total), interspersed with small fragments of coloured glass paste.

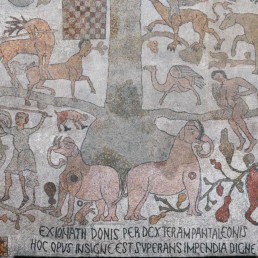

The four Latin inscriptions in the mosaic itself also provide us with the main information about the mosaic’s author, who commissioned it and when it was made.

The first inscription, which can be read at the start of the cathedral, almost acts a business card for all those who enter: it states the name of the mosaic’s artist, Pantaleone, as well as that of the man who commissioned the work, Jonathas, Archbishop of Otranto.

The remaining inscriptions indicate 1165 as the year in which this extraordinary undertaken was completed and commemorate the then reigning monarch, King William I of Sicily.

The mosaic was made in just two years, a very short time for the completion of such an extraordinary visual work, as evidenced by the same inscriptions, which refer to it as “eminent”.

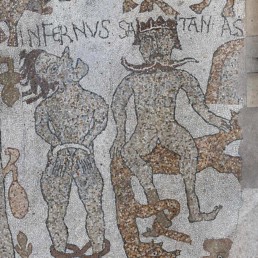

Not only do these latter inscriptions offer important information about the mosaic, they act as important links that connect the different spaces into which the liturgical space is divided: the lower part of the nave, which was reserved for sinners and catechumens (those being taught the principles of Christianity with the aim of being baptised); the upper part of the nave, reserved for the faithful; the presbytery, a space reserved for the clergy, deacons and lectors; and the apse, a space for the officiants.

The story of the “stone book”

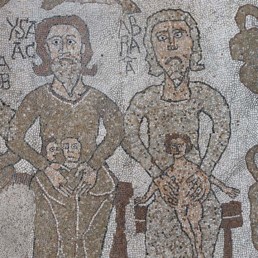

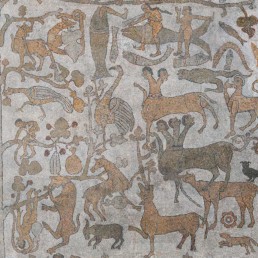

In Romanesque art, the floor of a church is a space dedicated entirely to earthly images, and the Otranto mosaic is no exception; this is why Pantaleone includes animals, both real and imaginary, inspired by Medieval bestiaries, heroes from chivalric literature, mythology and the cycle of the months, which was considered extremely lucky during the Middle Ages.

The mosaic also features characters and episodes from the Old Testament, prophets, angels, and demons. However, as a floor mosaic, something which by its very nature is designed to be walked on, figures of worship such as Christ and the Virgin Mary do not feature.

The pilgrim who enters the Cathedral for the first time may experience a feeling of disorientation and chaos due to the sheer number of images and figures that populate the mosaic as a whole, alternating and intertwining among the foliage of this majestic tree.

This chaos, however, is only an illusion, and in fact prepares the pilgrim for wonder and amazement.

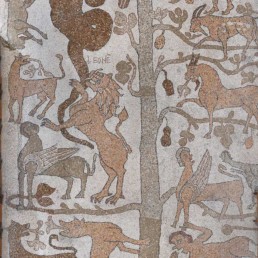

The main protagonist of the Otranto mosaic is the Tree of Life, an ancient iconographic symbol common to many cultures, but which here serves as a symbol of Christ: the Way, the Truth and the Life.

The tree is complemented by other trees in the transept as part of its telling of the History of Salvation, a singular history recounted by Pantaleone’s magnum opus with synthesises the human experience from Sin to Grace.

The Tree of Life’s imposing trunk, which extends down the length of the nave, also has an important function.

The trunk is designed as a central axis of the middle nave and as a significant guideline that leads and accompanies the faithful from the entrance of the Cathedral to the altar.

The momentum of the narration leads from the entrance to the “sanctuary”, or the presbytery, the place of the Eternity of the Creator’s Wisdom, and to the apse, the place of Resurrection. The trunk orientates the gaze to the East, the very East from which the Sun rises every day and towards which the pilgrim can orientate themselves in their own journey towards Christ, the Sun of Righteousness and Peace.

The Otrantine Tree performs the same functions entrusted to the typical aisles of other cathedrals,

that of taking the homo viator by the hand and accompanying him on his spiritual journey, amidst

warnings and teachings, to which the depictions and scenes refer.

The Tree, therefore, marks the path of the soul, a pilgrim among the joys and trials of life, to reach

the heavenly homeland and the fullness of paradise.